poche

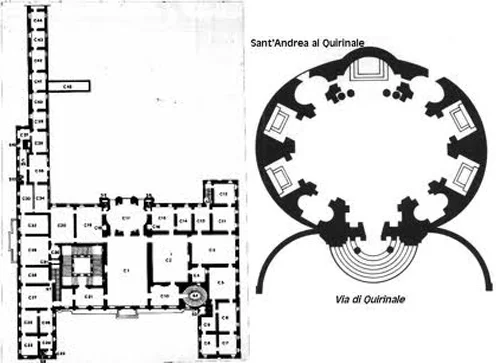

Pronounced with an exaggerated accent on the final "e", "poche'" is a French architectural term for the all the stuff that is inside the walls between spaces. In architectural drawings, it is the stuff blackened in on the plans.

John Soane's House Museum in London

For typical construction where all the walls are about the same thickness and both sides run parallel to each other, poche' isn't really a design element. However, back in the days of predominantly stone masonry buildings, the thickness of stone walls gave them a relative presence that allowed for their manipulation as architectural entities.

niche spaces in the poche'

The simplest treatment of poche' and the base cause of the term’s use is when architects describe carving into a wall to create a niche. In those cases they may describe using the poche' space of the building. In a sense, it is carving into the "solid" mass of the wall space even though in modern construction this space of the wall is certainly not stone or solid mass.

Baroque plans are especially rich in their interesting manipulation of poche' to create geometrically shaped rooms. The resultant wall shapes between rooms, the poche', takes on a presence that is as "shaped" as the rooms and certainly more interesting than simply the space between two wall surfaces.